Lessons of the Cherry Blossom: Japanese Woodblock Prints

In 1912, over 3,000 cherry trees were bestowed upon Washington, D.C., by Tokyo in an effort to enhance the growing friendship between the United States and Japan. The trees were planted along the Tidal Basin in West Potomac Park, where they continue to be admired every spring during cherry–blossom season. In celebration of the 100th anniversary of this diplomatic gift, the Norton Simon Museum presents Lessons of the Cherry Blossom: Japanese Woodblock Prints. The exhibition features 16 prints from the Museum’s permanent collection, several of which have not been on view before, including three rare sets of uncut double prints by Utagawa Hiroshige and works by Totoya Hokkei and Chōbunsai Eishi. Two prints from Katsushika Hokusai’s Rare Views of Famous Bridges series, which have been in storage for over 30 years, are also being exhibited.

Lessons of the Cherry Blossom explores the significance of the cherry blossom (sakura) in Japan. The sakura has long been an important symbol in Japanese art and literature, so much so that by the eighth century, the general term for flower (hana) in poetry referred to the cherry blossom. Its significance in Japan is due, in part, to its evanescent beauty, which resonates with the Buddhist ethos of life’s illusory nature. The cherry tree blooms en masse during the spring, and its blossoms die within a week of their flowering, making their beauty both intense and short-lived. It is during this time that friends and family gather to take part in hanami, or “flower viewing,” by traveling to districts populated by cherry trees.

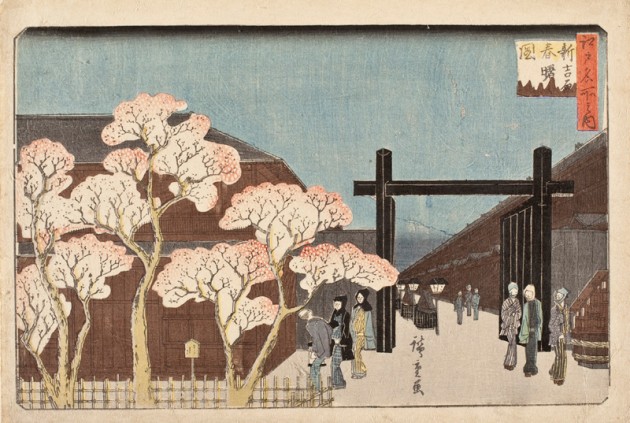

Cherry trees typically grew in remote mountain areas; however, under Shogun Yoshimune (1716–45), cherry trees were planted in cities as a means of urban beautification and of demonstrating the government’s benevolence. Areas such as the city at Asuka Mountain, Goten Mountain at Shinagawa and along the banks of the Sumida River and the upper Tama River became famous for cherry-blossom viewing. The history of the sakura reveals that almost all of Japan’s famous cherry-blossom spots were not natural, but the result of human effort to beautify the landscape.

Prints featuring cherry-blossom viewing became popular in the early 19th century, when increased travel, combined with the desire of publishers to find a new subject not based on changes in the clothing fashions of courtesans and geisha, resulted in a commercial market for landscape prints depicting famous places, or meisho. While most of the prints included in the exhibition focus on images of meisho, a few prints feature bijin, or beautiful women. Artists often conflated beautiful women and cherry blossoms, as both were symbols of the temporary nature of beauty and life.