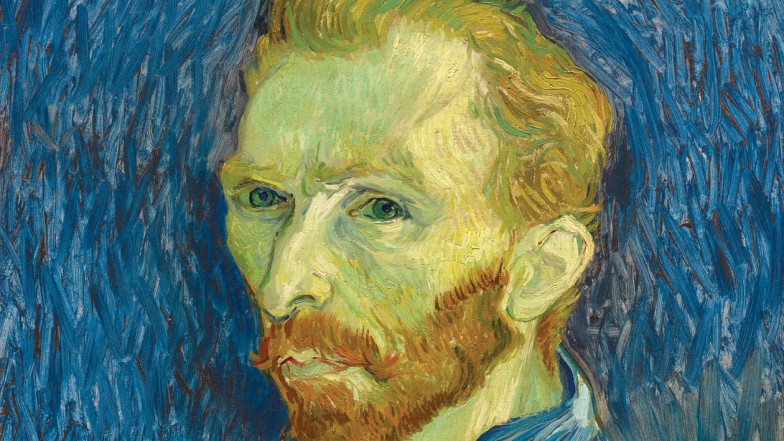

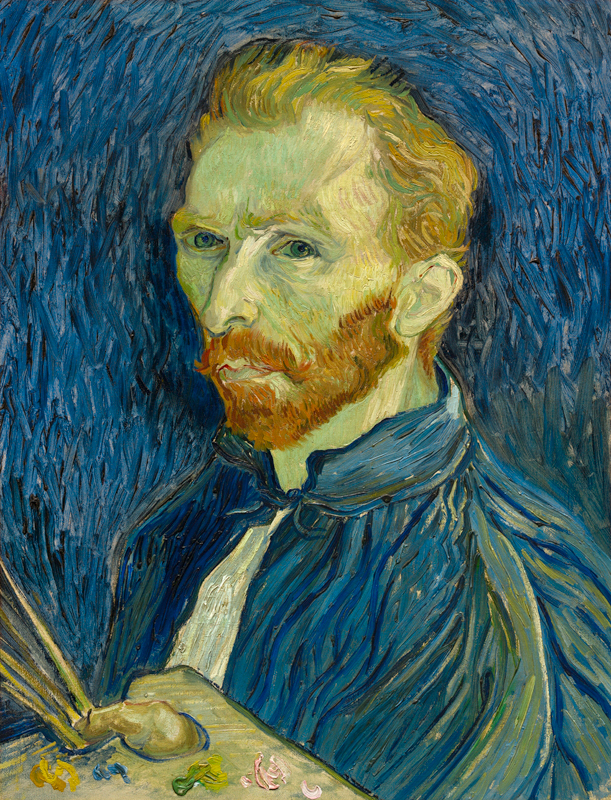

Van Gogh's "Self-Portrait," 1889, on Loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington

As part of the exchange series that brought Raphael’s Small Cowper Madonna and Vermeer’s A Lady Writing to the Norton Simon Museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., will once again lend a monumental work. This December the Museum welcomes Vincent van Gogh’s hauntingly compelling Self-Portrait, produced in late August 1889, less than a year before his untimely death at age 37, in July 1890.

After voluntarily committing himself in May 1889 to the mental asylum Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at Saint-Rémy in the south of France, the tormented Van Gogh began the isolated and recuperative process of calming the delusions, paranoid panics and poor health that had plagued him for much of his adult life. Only six months before, he had quarreled with his dear friend Paul Gauguin in Arles and then severed part of his own ear in a fit of desperation and despair. Despite these lapses in his mental health, the sustained physical damage to his body from a lack of eating, as well as his seizures, which were diagnosed as epileptic, Van Gogh spent this year of self-imposed confinement producing some of his most revered masterpieces. Save for brief periods during which he was banned from his studio at the asylum—at one point he had tried to ingest his oil paint during an attack—Van Gogh managed to create more than 140 paintings in the 13 months he spent there. These include iconic images of peasants, irises and olive trees, along with his final three self-portraits, one of which is the Washington painting.

The jolting, poignant Self-Portrait is one of the last renditions of Van Gogh’s penetrating interpretation of his own visage. Only three of his 36 self-portraits depict him as an artist, holding his palette and brushes. With his wounded ear turned away from the viewer, he confronts his own gaunt image, full of introspection and intensity. Unable at this point to confront other patients, or reality itself, he assumes the dual role of model and artist. By September 1889, after creating Starry Night (now at the Museum of Modern Art, New York) and painting the wheat fields that could be seen from his rooms at the asylum, he wrote to his brother Theo in Paris about two self-portraits he was painting:

So I am working on two portraits of myself at this moment—for want of another model—because it is more than time I did a little figure work. One I began the first day I got up, I was thin, pale as a devil. It is dark violet blue, the head whitish with yellow hair, thus a color effect. (Van Gogh to his brother Theo, September 5–6, 1889)

This dark-violet picture is generally thought to be the National Gallery’s Self-Portrait. The other portrait could be one in a private collection, or the one now at the Musée d’Orsay, his final self-portrait. Over time, Van Gogh’s “dark violet blue” has changed to a deeper blue, as is the case with certain pigments he used. The rapid, almost violent, thickly painted brushstrokes in the background shimmer restlessly in contradiction to the artist’s deeply penetrating and steady stare. The emerald highlights in his face, the blue of his smock and the golden yellows of his hair and beard are all echoed on the palette he holds in his right hand—pigments that had only recently been ordered and sent as a care package from his brother. The rapidity and persistent repetition of linear movement belies the amount of forethought and precision that Van Gogh applied to this composition; he used utmost restraint to circumscribe the nose with a bold green outline, and he calculated the effects of the juxtaposed yellows, blues and reds, sometimes picked up by his brush on the same swipe.

Locals knew him as the “redheaded madman,” and yet during his lifetime, he articulately composed hundreds of moving letters (in Dutch, French and English) that demonstrated his love for his family and fellow man, of nature, literature and art. In 10 short years, from 1880 to 1890, he painted almost unceasingly; more than 850 oil paintings are attributed to him today. One can only imagine his legacy, had he lived beyond his short 37 years.

Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait will be on view in the Museum’s large 19th-century gallery alongside another painting he executed at Saint-Rémy, Mulberry Tree, from October 1889 (created only two months after the Washington painting), as well as other earlier paintings by Van Gogh in the Norton Simon collections. The Self-Portrait will be displayed through Monday, March 4, 2013, and then will return to its home on Constitution Avenue in time to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth, March 30, 2013.

Featured Media