Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) was the most influential artist of the 20th century. Across eight decades and countless media, he pursued new modes of representation in a career characterized by ceaseless change and experiment.

Born in Málaga, Spain, Picasso studied in Barcelona and Madrid before settling in Paris. His early manner—marked by the influence of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the bohemian milieu of Montmartre—was swiftly supplanted by the melancholy palette and gaunt figures that define the work of his so-called Blue Period (1901–1904). A new lyricism and interest in Classical tradition emerged in the Rose Period (1904–1906), which, in turn, gave way to the fractured geometry and assertively painted surfaces that defined Cubism in its various forms.

Picasso’s co-creation (with Georges Braque) of this radical new approach to representation was his most significant contribution to the history of Western art and ways of seeing. Cubist paintings, prints, and sculptures are not fully abstract—that is, they are not entirely divorced from the observed world. They do, however, trouble the relationship between the object and its image, rejecting likeness as the defining feature of visual representation. Although the properly Cubist phases of Picasso’s stylistic development lasted only to the end of World War I (when he, like many of his colleagues, participated in a widespread conservative turn known as the rappel à l’ordre), the great Cubist experiment would influence his work for the rest of his life.

SHOW MORE

From the 1920s onwards, Picasso’s career is less easily divided into periods on stylistic ground; the artist pursued drastically different formal explorations simultaneously, turning out spare, elegant etchings of mythological scenes, for example, at the same moment when he was painting tortured portraits in oils. Perhaps for this reason, art historians often carve up the last five decades of his career along what Picasso’s longtime secretary Jaime Sabartès once called “the curves of his love.” There are the so-called Olga pictures, painted in the first decade (1918–1928) of his marriage to the ballerina Olga Khokhlova. There is a group of sensuous paintings, prints, and sculptures associated with Marie-Thérèse Walter, his mistress and model from 1927 through the mid-1930s. There are the angular, even agonized, portraits he painted of Dora Maar, the Surrealist poet and photographer who was his companion through the dark years of the Second World War. And the gracious, witty work of his postwar “époque Françoise” (1946–1953), spent on the Riviera with the young artist Françoise Gilot. Finally, there are the late works—many of them meditations on his relationships with masters past—produced during Picasso’s final two decades, under the care of his second wife, Jacqueline Roque.

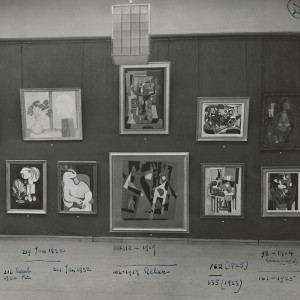

Works in the Norton Simon collections represent every aspect of the artist’s production: from a circa 1901 drawing of a Montmartre cabaret to a brash pastel head dated 1971; from a monumental chalk to an earthenware plate; from a Rose Period bronze to a riotously colorful portrait of Marie-Thérèse Walter. The holdings are particularly rich in prints, including intact sets of such famous series as the Suite Vollard and the Tauromaquia, as well as an important group of linocuts, rare impressions of Blue Period and early Cubist prints, and one of the deepest troves of postwar lithographs anywhere in the world. Over three decades of collecting (from 1955 to 1984), Norton Simon acquired more works of art by Picasso than by any other artist but Goya—885 in all. The vast majority of these today belong to the Norton Simon Museum and its associated foundations.

SHOW LESS