X-radiography

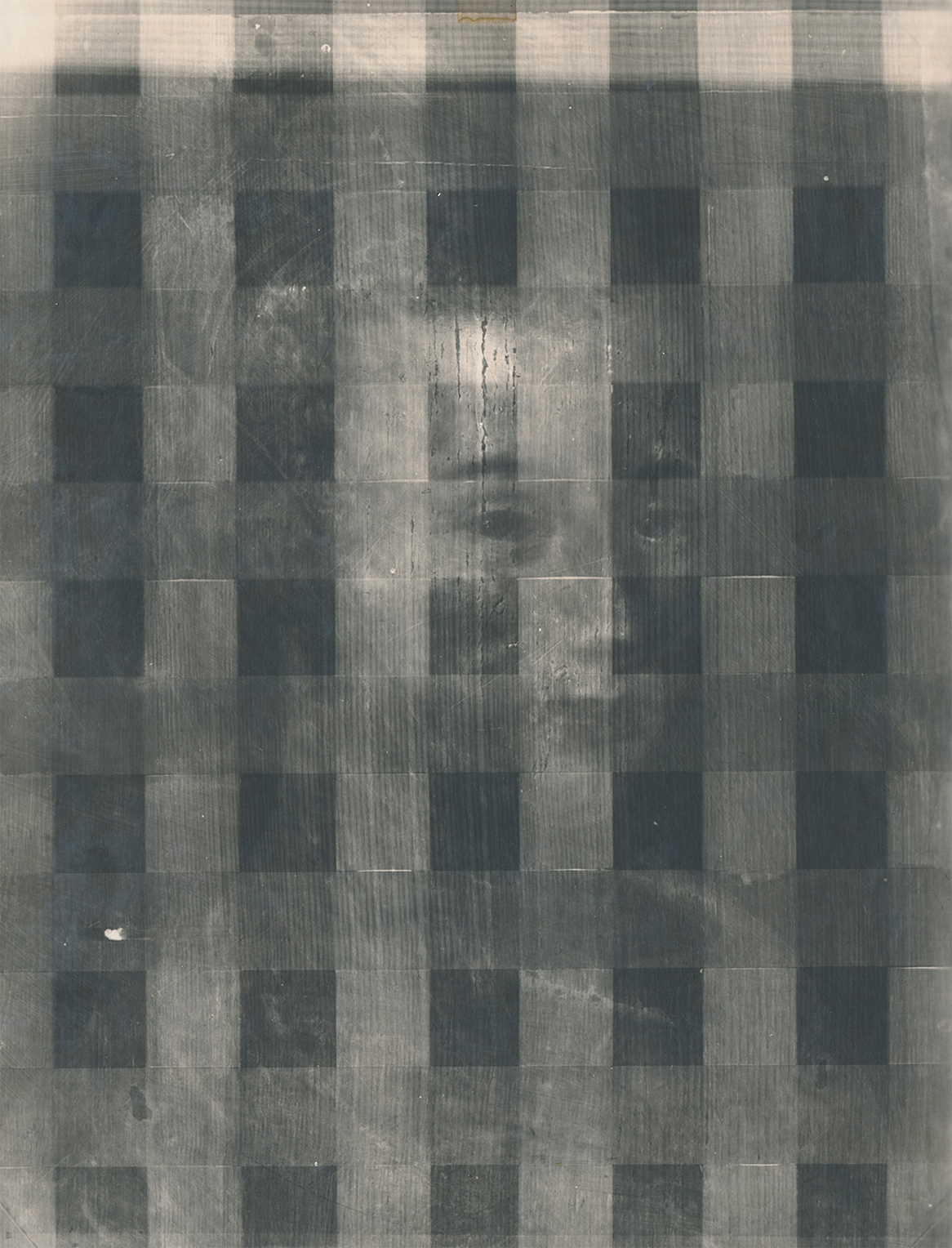

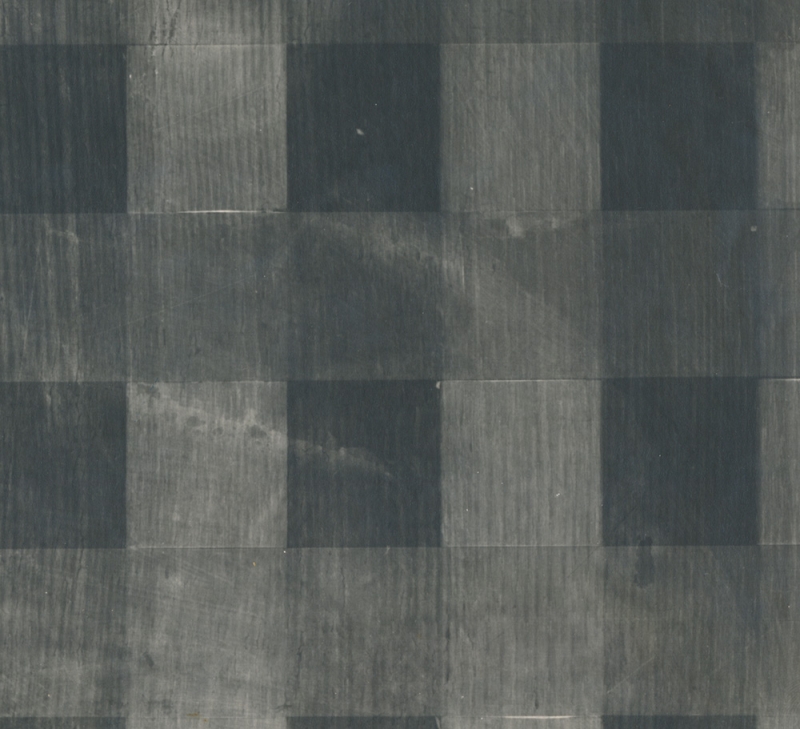

X-radiography—the same technology used in medical diagnostics—has become an important investigative tool for the study of paintings. When exposed to X-rays and processed into an X-radiograph, low-density elements such as carbon are rendered transparent, while elements of greater density—such as paints containing lead-based pigments—slow down or block the penetration of high-energy rays and are thus made visible in the resulting image. In the Norton Simon Museum’s painting, the X-rays pierce all the way through to the cradle (fig. 1), a grid of wooden slats attached by a restorer to support the panel from behind. They also expose a shadowy form in the lower right quadrant of the painting (fig. 2). Angled up toward the figure’s chin, the form’s relatively lighter tone suggests that it belongs to a layer of paint hidden beneath the visible surface.

This evidence of an obscured element encourages further technical investigation into the concealed layer.

Figure 1: X-radiograph of School of Fontainebleau (French, 16th century), Portrait of Diane de Poitiers (?), c. 1550, oil on panel, 16-3/8 x 12-7/8 in. (41.6 x 32.7 cm), Norton Simon Art Foundation, from the Estate of Jennifer Jones Simon, M.2010.1.174.P

Figure 2: Detail of the panel’s lower right quadrant